In 2011, Eric Reiss published “The Lean Startup,” which quickly became a dominant mode of thought in the technology and entrepreneurship community. The book includes examples from the preceding decade of companies such as Dropbox proving what is called their “value hypothesis” by creating a short demonstration video and sending it to potential customers. They collected feedback and email addresses of people willing to pay for such a service and were quickly able to attain funding.

In 2011, Eric Reiss published “The Lean Startup,” which quickly became a dominant mode of thought in the technology and entrepreneurship community. The book includes examples from the preceding decade of companies such as Dropbox proving what is called their “value hypothesis” by creating a short demonstration video and sending it to potential customers. They collected feedback and email addresses of people willing to pay for such a service and were quickly able to attain funding.

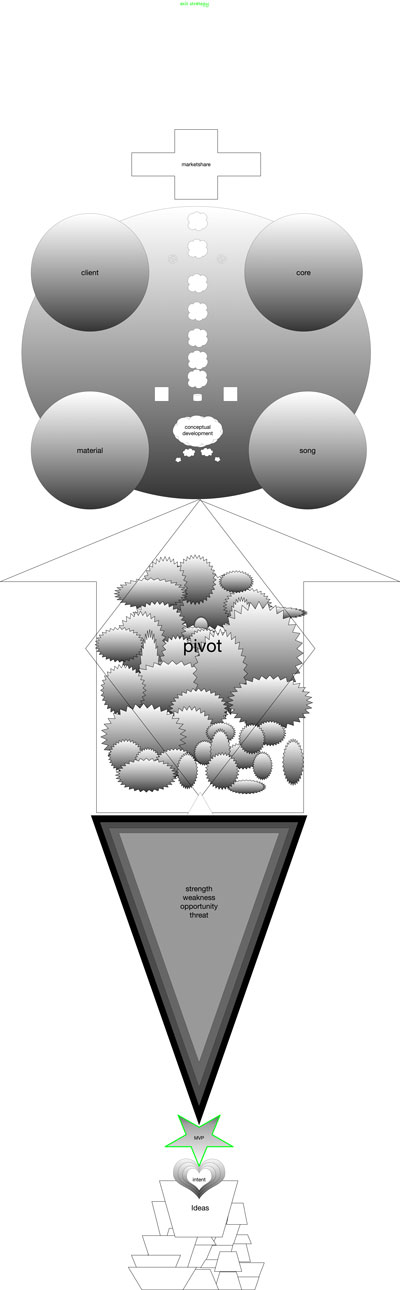

The Lean Startup Methodology is one of the primary texts defining how and why a technology startup measures and replicates its own success. They employ rapid iterative testing of stripped down products that enables a team to measure the viability of the product once it goes to market. Thus, rather than spend a year and a lot of money developing a finished product that nobody wants, you attempt to create many inexpensive iterations of the idea, test them, and measure their results. It is similar to how a scientist would go about proving a hypothesis.

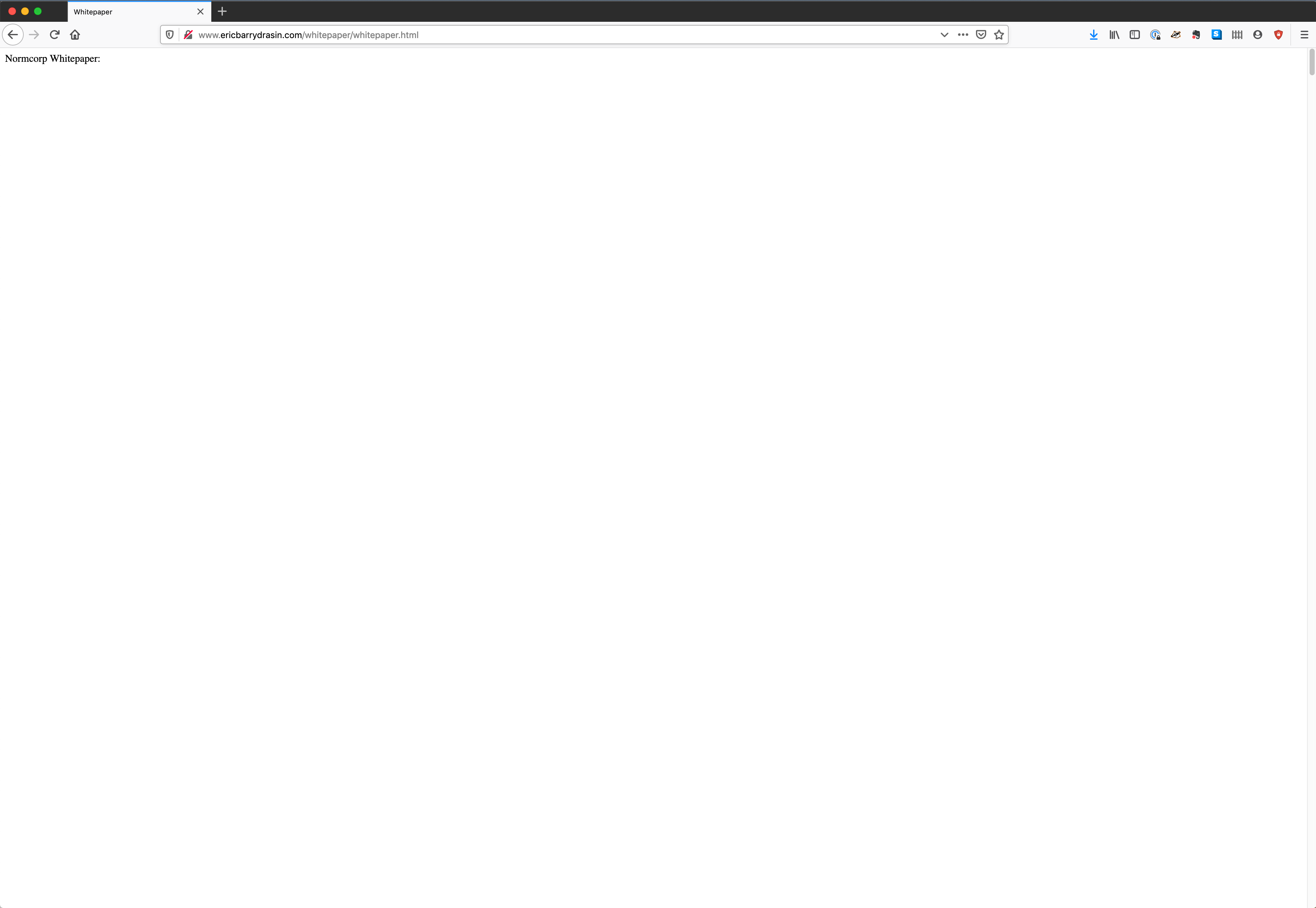

Lean Startup Strategy Control provides the top level rubric for how one ascends the lean startup methodology from inspiration to Exit Strategy. The process starts in the free form associative space of idea generation. When an idea can harness intent, it can formulate what is called a

“Minimum Viable Product,” the vehicle of growth, and begin its ascent. Through careful analysis of potential threats, it performs a SWOT analysis, which measures its relative strength, weakness, opportunity and threats relative to the competition.

This leads to the process of testing the MVP in the market which results in pivots, or the transformation of the MVP into its higher form. This process of conceptual development and testing moves through the various spheres of influence until marketshare is reached. Marketshare is the point where the MVP can prove its merits, and is ready to begin its Exit Strategy in earnest.

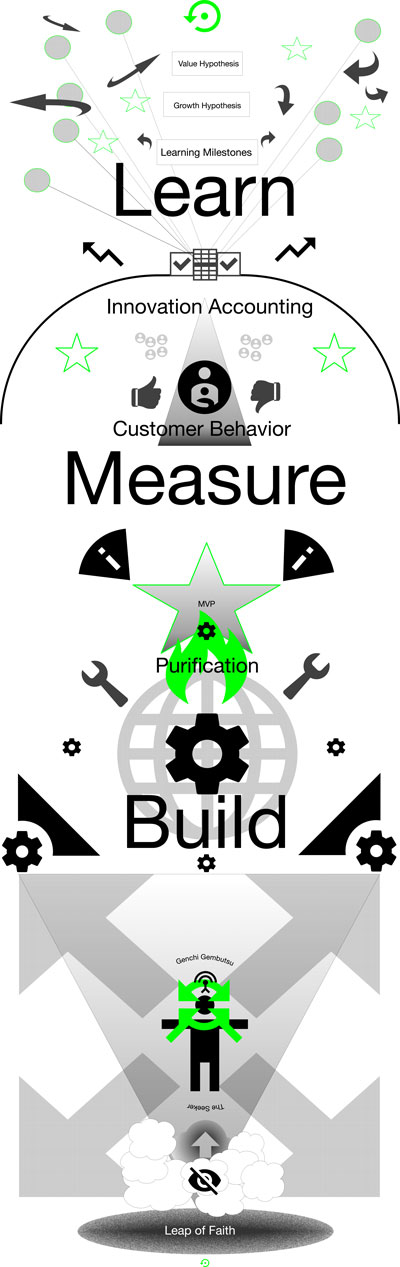

The Exit Strategy is the point of consummation, where the MVP has reached its purpose and can now release it’s previous form and merge with larger pools of capital.

Engine of Growth

Engine of Growth